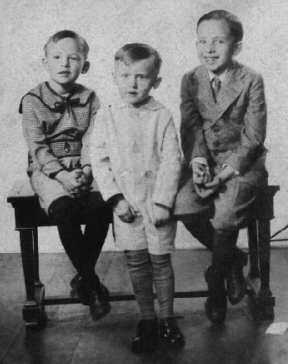

Mr. Miles Griffith Beard On April 14, 1918, at 1838 Lockwood in Indianapolis, Indiana, a big baby boy was born at home to a Hoosier schoolmarm. He was a large baby with wide shoulders, and the physician had to stand at the end of the bed and pull the baby from his mother's body. His mother named him Miles. The first year of Miles' life, he and his parents lived with his dad's parents in a tiny rural place in Indiana's cornbelt called "Owasco," where the creek was the "Wild Cat" and the road was "Jerkwater Road." It's south of Delphi, just north of Rossville, and about 20 miles east of Purdue University. His grandparents had a 100-acre farm and raised corn and hogs. The neighboring farms were owned by various paternal family members: BEARDs, HUFFORDs, CRIPEs, and MOREs. As a kid, he often visited family in Owasco and Rossville. Many of his relatives in the Rossville area were German Baptist Brethren; Miles, however, never had much appreciation for organized religion. He and his parents were living in Wayne Township, Fulton County, Indiana, when the 1920 Census was taken on January 6, 1920. The Census lists Miles as one year and nine months old; it lists his father as a 23-year-old farmer on rented land and his mother as 28 and not employed outside the home. (1920 U.S. Census; ED 78; Sheet 2-A; lines 31, 32, 33.) In March of 1920, Miles became a big brother when his brother Max was born; when Miles was 3 1/2, his brother Bruce was born. The three brothers were always close.

When Miles was quite young, the family lived in LaGrange for a while. In the 1920s, they moved to South Bend, 1216 Kinyon Street, a half-mile west of the St. Joseph River and a mile west of the University of Notre Dame. Among the neighbor families were the GOHEENs, the MARSACs, and the BATCHELORs. One of his childhood friends was Martin "Tink" Tarnow (1917-1998), who grew up two blocks from Miles and who went on to found Martin's Super Markets in the Michiana area. As boys, Miles and Tink sometimes worked together bagging potatoes for a local grocer. When he was growing up, Miles' mother had some serious health problems. During times when she was sick, her three boys would stay with various relatives. The one he would stay with was his mom's sister Linnie; Miles had been born at his Aunt Linnie's home and was named after Linnie's husband. ... Aunt Linnie was quite stern; almost certainly, she beat Miles badly. His memories of her were not fond. His brothers stayed with other relatives, each with a different relative. In 1930, Miles' dad was working as a gravel contractor. According to the 1930 Census (April 8, 1930), the other dads in the neighborhood were factory laborers, a barber, a gas station manager, a carpenter, an excavation contractor, a metal polisher, a tool maker, a mail carrier, a millwright, a sheetmetal worker, and a night watchman. (1930 U.S. Census; ED 71-9; Sheet 7-A; lines 11, 12, 13, 14, 15.) During the 1930s, his dad worked at the nearby Studebaker Corporation. Miles' childhood neighborhood would have smelled of beer and bread and the St. Joseph River: His home was four blocks northwest of a bread factory, and four blocks northeast of the Muessel Brewing Company factory, located on Portage Avenue at Elwood Avenue. In late 1936, Drewrys Beer bought the brewery. In the 1920s, Miles went to Muessel Elementary School in South Bend, Indiana. He graduated from South Bend's Central High School in 1936, in the middle of the Great Depression. He never played sports; he was one of the "geeks" in high school. He was awarded a full merit scholarship to University of Chicago. He was there for one year, and it is something that he was so proud of that he talked about it for the rest of his life. During his time at U. of Chicago, he lived with his mom's sister, his Aunt Alice. She had a ground-floor apartment on East 67th Street, a mile south of the university and a dozen blocks west of Lake Michigan, directly across from the 500-acre Jackson Park. Miles slept on the sofa in his Aunt Alice's front room, walked to and from the campus, and carried candy bars to serve as his meals during the day. At U. of Chicago, he was vaguely involved with the intramural football team. At the time, the university did not have a team that played other colleges, but they had several intramural teams, and Miles played on one. His description was that he played "14th string" on his team; he joked about it and thought it was funny. Even on an intramural team, Miles was not a jock. He lost the scholarship at the end of the year, moved back to his mom's house on Kinyon Street in South Bend, worked for a while in a greenhouse and at a factory, and tutored Notre Dame students in math. Math was Miles' special gift from God.

December 23, 1940, Miles enlisted in the Indiana National Guard. On January 17, 1941, in South Bend, IN, Miles was added to the role of those enlisted in the U.S. Army, in the Army Corps of Engineers. Added the same day, also to the Corps of Engineers, was Miles' friend Paul Elden Stafford (1921-1996). Paul was the age of Miles' younger brother Bruce. Miles had enlisted in the Guard because he knew that otherwise he would be drafted. By enlisting, he had some choices. His Army enlistment record describes him as 72 inches tall, weighing 160 pounds, with one year of college, single and without dependents. After basic training, initially there was a plan for him to go the route of an officer. He was at officer candidate school. Exactly what happened is unclear; he ended up at Ft. Bragg, training troops. His part of the training was to take the men out on 20-mile hikes, something they did at the end of the training. Day after day, he took new soldiers out for 20-mile hikes. ... How do you get men to walk 20 miles? According to Miles, "A little at a time. Make sure they get to rest and have water. If a man sits down and says he can't walk any more, you let him rest for a while; then you remind him that, if he doesn't finish that day, he'll have to do it all over again the next day, and he won't get credit for any of the miles he already walked." Also in the 1940s, he was stationed for a while at Biloxi, Mississippi. Ultimately, he became a Master Sgt. and was stationed on Manila in the Philippines. In Manila he had a driver, his own cook, and a male secretary. He said that his secretary (an Army man) could type faster than he (Miles) could talk. Among others whom Miles met while serving in the Philippines was the woman later known as Imelda Marcos. Miles served in the Philippines until late 1945. He was 27 years old and a Master Sergeant when he left the U.S. Army on December 27, 1945, with an Honorable Discharge, a Good Conduct Medal, an American Theater Ribbon with two Bronze Stars, an Asiatic Pacific Theater Ribbon, a Victory Medal, and a Philippine Liberation Ribbon. His military number was 20-540-467; Social Security number was 315-10-6764. (Military discharge papers, in PDF format.) When he left the Army, he imagined that he would take advantage of the G.I. bill, complete college, and become an engineer. Life didn't turn out that way. He returned to South Bend and lived with his mother on Kinyon Street. He began working at the Ball Band factory, then a subsidiary of U.S. Rubber, later owned by UniRoyal. He worked in the auto mats division and made rubber car mats. Miles ran a big machine called a vulcanizer. In his early years out of the Army, he also did college course work. Indiana University was already offering classes on an "extension" basis. Classes were held at various buildings thruout the South Bend area. Some of Miles' classes were held at the Mishawaka High School building, in the evening. He still was hoping that he could finish a college degree and become an engineer.

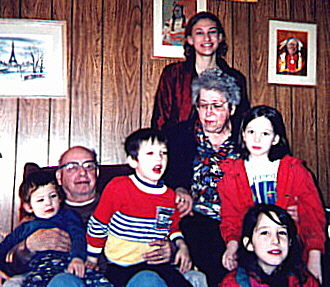

Thru a buddy known as "Mooney," he met the woman who became his wife. The buddy was dating a divorcée named Mary Jane; Mary Jane had an aunt named Elizabeth Ann who was just a little older than she. Mary Jane's aunt was also a divorcée with two young children. ... The woman who became Miles' wife had two daughters from her first marriage -- a five-year-old and a two-year-old. The two-year-old had never really known her own dad, and she was afraid. She wouldn't let Miles near her, and she wouldn't talk to him. ... Then one day he asked her if she wanted to go get some ice cream. Thereafter, she was his friend and biggest defender. She was a little girl wearing leg braces because she'd had rickets, and that day she "found her savior." Miles bought a little house in Mishawaka, in Normain Heights, a neighborhood built for W.W. II veterans, and in late 1949, in a Methodist church in South Bend, Miles married Elizabeth Ann. Ten months after they married, the first of four children was born to them; Miles named her "Alice," after his Aunt Alice. Over the next 14 years, Elizabeth Ann gave birth to Miles' three sons. He supported his family by working at Ball Band. For many years he worked the evening shift -- 11 pm to 7 am -- to earn another 15 cents an hour for his family. He spent the 1950s saying that leaving the Army was the worst decision he'd ever made. He had been well respected while he was in the Army, and he felt like a "somebody" then. In the mid-1950s, Miles welcomed his octogenarian father-in-law into his home for the last few years of the old gentleman's life. All he asked was that his father-in-law spit out the door when the old man chewed his tobacco! Miles enjoyed gardening. He grew roses and cross-hybridized his own iris. Until he no longer was physically able, he had his backyard filled with iris, day lilies, dahlias, poppies, lillies-of-the-valley, gladiola. He used to go fishing, even ice fishing -- not just for pleasure, but because there were times when the fish were needed to supplement the family food supply. In nice weather, he'd rent a row boat, row out into a lake, and sit for hours fishing. Sometimes his daughter would agree to go with him, if he would agree to buy her six candy bars -- one for each hour that she knew she would have to sit in a little row boat, in the middle of a lake, because that's how long her dad could sit in a row boat. Miles also collected stamps, from the time he was 8 years old, and he was a member of Northern Indiana Philatelic Society. There was a time when Miles was active in United Rubber Workers # 65, the labor union at Ball Band/UniRoyal. He was a pro-union man until 1967-1968 when there was a six-month strike. That strike killed his spirit and took every nickel he had, and the big "win" from the strike was a five-cent an hour raise, across the board. ... He always said that it was an ill-thought-out strike. The strike left him demoralized and angry. ... There were times during that strike when his family got food from some of his wife's relatives who were on welfare -- surplus cheese, canned powdered eggs. ... It was a humiliating time for him. By 1980, he retired from UniRoyal, after more than three decades of factory work. Over the years, he could be a grump and hard to get along with, and he didn't much care or give a damn; it's just who he was. He replaced the roof on his house; he replaced the furnace in his house, and he fixed his cars, all by himself. By necessity, he was a "jack of all trades." He lost his brother Max in 1988, and the loss was an unexpected shock. He lost his brother Bruce in 1990, after a long, painful illness. ... Miles and his wife made the drive to Mayo Clinic in 1990 to see his brother before his brother died, and then Miles had no more brothers, a reality that was a great sadness to him. For the last many years that he lived in his little house in Mishawaka, his activities were watching TV, drinking one beer a day in the evening, and sometimes sitting outside the backdoor of his house. ... His vision had been horrible for years and years, so bad that he stopped driving in 1970. He had what is known as "tunnel vision," and the "tunnel" of his vision began shrinking in about 1970. He was a man who lived with some regrets. As he told his daughter when he was 55, "There are sadder words than 'what might have been.' Sadder still is what WAS, but shouldn't have been." He did not live his life without sin or without mistakes. He was human. He once described his philosphy of life as, "God says that the choice is yours, and yours alone. But if you make the wrong choice, suffer, buddy, suffer." He accepted his suffering as a price paid for his wrong choices.

On March 21, 1999, Miles had a massive stroke. Three hours passed before help was called. His wife was in the room when he fell to the floor from the stroke; she opted not to phone 911. At the hospital, brain scans showed that he'd had at least one prior stroke some years earlier. The massive stroke left him with left-side brain damage, aphasia, and almost no use of his right hand, but he was able to resume walking with a cane. He was in an exceptionally weakened condition from early-1999 until late-2000.

On March 11, 2000, after months of anemia from blood loss, he had 10 inches of his colon removed because of cancer of the colon. Four days later, he had some heart problems. According to hospital nurses, Miles was so confused in March 2000 that he believed that his surgeon was the boy who lived down the street, and he would awake at night and tell the nurses to bring him his stamps. He had entered the hospital for surgery on an enlarged prostate. Once there, he was found to be anemic because of passing blood, and the surgery on his cancerous colon became more imperative than the surgery on the enlarged prostate. The prostate surgery was done after he recovered from the colon surgery. Still later in 2000, doctors told him that he had tuberculosis. The evening of September 19, 2000, he sat with his wife and their daughter, talking about the daughter's birth, half-a-century earlier: The family car had been left three miles from the house because Miles had locked the keys inside the car after driving to work. After work, he'd walked home, planning to walk to work the next day, taking the spare car key with him. Instead, in the wee hours of the night, his wife told him to get the car immediately because birth was imminent. In September 2000, as Miles and his wife reminisced about that long ago morning when their daughter was born, Miles reminded his wife of some details she'd forgotten, and they both spoke of "the dead twin." ... The next morning, he didn't know who his daughter was when she kissed his bald head and told him good-bye. Miles' vision had gotten so bad that some within the community referred to him as "the old blind man." By June of 2001, his wife said that he'd had bad double vision for many months, and could barely see. ... Father's Day 2001, he told his daughter, "There's one thing I always wanted to do in my life that I'm not going to get to do. Hike the Appalachian Trail from beginning to end." ... Cataract surgery later in the year returned some of his vision. New Year's Day of 2002, Miles sat with his daughter and watched the Rose Bowl Parade and the movie "Pearl Harbor," and he talked with his daughter about some of his World War II days. And New Year's Day of 2002 was the first that Miles' wife finally admitted to their daughter that Miles had had serious problems with memory loss for several years. Miles' wife explained that the problems had begun some years earlier, and that the times of "confusion" had only increased. She said that she hadn't admitted the problem to their sons, and that she hadn't told other people about it, that only she and her oldest daughter knew. She explained that sometimes Miles didn't know what year it was. She told of the time when Miles asked, "Which dog will be going to bed with us tonight?" ... Their last dog had died about ten years prior, and it had been even longer ago when Miles and his wife had had more than one dog. July 2003, Miles' daughter was in town to visit. Miles was in extremely poor condition and most of the time had no idea who his daughter was, the same daughter whom he'd named after his favorite aunt. Miles had not been shaved in so long that his beard was over an inch long, and his wife asked their daughter to shave the old man. Miles did not know who his daughter was as she shaved him. Thanksgiving 2003, Miles' oldest son was with him for a few days. The son was named for Miles' own grandfather. Many times Miles asked the son, "Who are you?" In the house where Miles had lived for 54 years, he asked his son, "Where's the bathroom?" Miles had become a vulnerable old man, at the mercy of those who would help and those who would hurt, and he no longer could tell the difference.

January 1, 2004, Miles fell and broke his left wrist at about 9 o'clock at night. An ambulance arrived, without sirens. Miles was able to walk into the living room of his home on his own power and walk to the stretcher. He left his house on the ambulance stretcher. His old bones were set, and he went back home. But, how does a man whose right hand is paralyzed and whose left hand is broken feed himself? How does he pull down his trousers to toilet himself? Miles' life took a quick decline with that broken wrist. He lost over 30 pounds in 2004. In November 2004, he was hospitalized because of a urinary tract infection. The hospital got him well, and he went back home, with antibiotics. Less than two weeks later, he was back in the hospital. This time, before he was carried out of his house on a stretcher, his wife told the ambulance attendants to remove Miles' wedding band. On January 3, 2005, three-and-a-half months before he turned 87, Miles was moved from the Mishawaka hospital to Fountainview Place Nursing Home, about a mile from the house where he had lived for 55 years. The nursing home physician diagnosed Miles as having severe vascular dementia with delusions, brain damage, and depression. The physician also determined that Miles had been dealing with being over medicated, being under hydrated, and being underfed. There were suspicions that Miles had survived abuse, but there was no proof. Miles was tight-lipped about whatever he had survived. The only clue Miles offered was how he interacted with visitors. Miles seldom had visitors, but the visitors he had fell into two distinct groups. With nursing home staff, other residents, and one group of visitors, Miles held his head up, talked some, and occasionally made jokes. With visitors from the other group, Miles dropped his chin to his chest, looked down, and seldom spoke. At Fountainview, Miles was treated with great dignity and great care. He had a view of grassy lawn and trees thru the window next to his bed. He dined with other seniors and watched geese that gathered in the yard outside the dining room. He "walked" the halls in his wheelchair. Occasionally he played Bingo; sometimes he and his roommate, Bernard, would watch a football game on TV. Miles napped a lot, and he enjoyed his one beer a day. He wore baseball caps to keep his bald head warm, and he enjoyed the flowers his daughter sent weekly. The staff and other residents at Fountainview grew to like the old man with the dry sense of humor who would sit in the middle of the hall, drink his nightly beer, and tell his "beer stories." On occasion, he would talk about his daughter and wonder where she was, even as she sat with him. One day he visited with two middle-aged women and one dog, and he told the women that Alice had given him the shoes he was wearing, "the most comfortable shoes I've ever had." In that moment, he did not know that one of those middle-aged women wearing tri-focals was his daughter. He had a visit from another middle-aged woman whom he'd known since she was two-years old. The woman said, "Hi! It's Mary Beth," and then quickly added her childhood nickname: "It's Blinky." Miles looked at her and said, "No. You're not Blinky. Blinky was thin." The woman who for years had walked next door to share with Miles her homemade apple pies and keflies just laughed and said, "Yes. It's me. I just got older and fatter." Miles died March 23, 2006, just after seven o'clock in the evening. It was his sixth day without hydration or nutrition, as ordered by the woman who had taken durable power of attorney. The woman demanded that nursing home staff keep her orders secret while Miles lay dying. Nursing home staff who had grown to like Miles were horrified by the orders. The day before the orders were given, Miles had been out of bed, dressed, and able to get around in his wheel chair. [Story here.]

Miles Beard was and is my father. When I was a little girl, one of the stories he would read to me was Longfellow's "Hiawatha." There's a part of Longfellow's poem that deals with how a family member remains a family member even after death. At the time my father was reading that poem to me, he would have been dealing with the loss of his own mother, accepting how she remained his mother even though she no longer had earthly form. These days, I like to think that my father's in heaven, joking with his brothers. I imagine his brother Max greeting him formally with, "Hello, Miles," and his brother Bruce, with a big smile and with suspenders holding up his baggy pants, saying, "What took you so long?" ... My dad would have said, "I had a longer tour than the two of you. You two got off easy." When I was a little girl, I would sit on his shoulders and hold onto his ears as he'd walk around the block holding onto my ankles. When I was a little older, I'd laugh as he would read O'Henry's "Ransom of Red Chief" to my brother and me. When I was in grade school, I was seriously allergic to poison ivy; Dad kept the yard cleared of poison ivy, but I kept getting it. Then Dad realized it was because neighbors would burn poison ivy with other yard weeds, and I'd be exposed to poison ivy oils from the smoke wafting thru the neighborhood. Dad went door-to-door to explain his daughter's allergy and asked neighbors not to burn poison ivy; he offered to come to remove any poison ivy if they would just call him. His efforts ended my serious outbreaks of poison ivy. Dad's own dad died when I was a teenager; my father took me from store to store hunting for the dress that he felt would be "politely proper" for his daughter to wear at his own dad's funeral: Dad decided on a pale yellow shirtwaist dress and said, "You'll be the prettiest granddaughter there." And I remember one of his classic lines from when I was a teenager: We were discussing religion, and I asked if he believed that the Virgin Mary truly did become pregnant while still a virgin. He paused a moment, seemed to think, and then said, "I don't know. But if YOU ever come home in that condition, you'd better have a better excuse!" During my undergraduate years, I still lived at home; for a while, I worked as a bank teller. One day I was exactly one hundred dollars short when I balanced my drawer. I was distraught -- not so much because I'd lost the bank's money, but because I feared people might think that I'd stolen the money. When I got home from work, I explained my fears to my dad. Like me, Dad didn't know how I'd lost the money, but he had no suspicion that I'd stolen it and said, "Alice, if I never taught you anything else, I'm sure I taught you that stealing one hundred dollars is beneath you!" In my father's final years, he was brain damaged, delusional, depressed, often dehydrated, anemic for many months in 1999, and frequently over medicated. He was often confused, and there were some people working to make him even more confused. No matter what he remembered, I remember my father. A father is not a fungible; you get what you get. The father I got was Miles Beard. Alice Marie Beard,

|

For Miles' pedigree, For

Miles' end of life FUNNY Before Miles was two years old, instead of a pony, he rode a pig named Pollyanna. The pig was his dad's prize brood sow in Fulton County, Indiana. When Miles was a kid, he ate geranium leaf sandwiches made by his neighbor Mrs. Marsac. Another favorite was a mustard sandwich: just plain bread and lots of yellow mustard. When Miles was a training sergeant in the U.S. Army, he took his turn leading morning exercises. He'd hold up his hand, stick out a finger, bend his finger up and down, and call out, "One-two-three-four." And that was his morning exercise for the troops. When Miles had young children, he paid ten cents a bag for every bag of chickweed that a child pulled from his garden. The chickweed never ran out. Miles believed that Drewrys beer was

good beer. Conversation when Miles was 87, and working at moving his feet: "Do you need new shoes?"

|

|||||||||||

STROKE SURVIVIVAL: The key factor to surviving a stroke and to limiting its damage is time. The main treatment (tissue plasminogen activator, known as "tPA") must be given within three hours to do any good. And the sooner it is given, the more good it can do. Stroke is a medical emergency. Here are the warning signs:

Time lost is brain lost! |

||||||||||||