The War

for one man,

and for one little boy

- by Alice Marie Beard |

Much of Dyonizy Ivanowicz' life was

determined by having been born on a strip of land that

was contested for generations.

He was born in 1914 in a small village called

"Dubatovka" which was near the larger village

of "Morozovichi." (The name

"Dubatovka" means something like "place of

the oaks," and the name was used for more than one

small village.) In Morozovichi, there was an Orthodox

church that is listed in records at the National

Historical Archive of Belarus as "Morozovichskaya

Rozhdestvo Bogoroditskaya Church" of the Novogrydok

district. The village of Morozovichi is northwest of the

city of Baranavichy (population 173,000 in the year 1995) and

southwest of the city of Novogrudok (population 30,800 in the year 2004).

Approximate latitude and longitude of the village of

Morozovichi are 53 degrees 32' north, and 25 degrees

34' east.

Sidebar

geography lesson:

The village of Morozovichi

was in the volost of

Koshelevskaya. A volost was a

small administrative area in Eastern Europe

similar to what in the United States in 2010 is

known as a township. A volost was part of a

larger administrative unit called an uyezd;

the uyezd that the volost of Koshelevskaya was

part of was the uyezd of Novogrudok (not to be

confused with the city of Novogrudok which itself

was part of the uyezd of Novogrudok). The uyezd

of Novogrudok had (at least ) 23 volosts. An

uyezd was part of a guberniya, a large

regional area or governorate; the uyezd of

Novogrudok was part of the guberniya of Minsk.

The uyezd of Novogrudok was one of nine uyezds in

the guberniya of Minsk. This system of villages

> volosts > uyezds > guberniya existed

from 1843 until 1918.

By 2010, the area is part of the oblast

or voblast of Hrodna, and Grodno is the

administrative center of Hrodna. Hrodna is one of

six oblasts in Belarus. |

When Dyonizy was born in 1914,

that area was a part of czarist Russia. His father, Ivan,

was taken from the family in 1918 as a result of the

Russian Revolution of 1917. Because his father had worked

for the White Russian Army, the Soviets sent his father

to Siberia.

Before 1920, when Dyonizy would have been six years old,

his mother moved the family to Pinsk (population

130,000 in the year 1999). In 1920, Pinsk became part of

Poland as a result of the Polish-Soviet War.

Dyonizy's mother had seven children and no support.

Dyonizy begged for food from soldiers on the streets and

was prevented from having any schooling because there

were no public schools and his mother had no money to pay

the school master. As a consequence, Dyonizy was

illiterate

In 1936, he joined the Polish Army for two years. In 1939

he rejoined because of the threat of war to his country.

His army unit was stationed in western Poland. The

Germans invaded September 1, 1939. When it became obvious

that they were losing, his unit retreated east. The unit

broke into smaller and smaller units so as to be less

noticeable until finally those Dyonizy was left with

decided to go as individuals. Dyonizy met a farmer and

exchanged clothes. Had Dyonizy been caught in Polish

military clothes, he could have been killed.

He walked east until he reached a train yard. He met a

train engineer who agreed to let him ride the freight

train east to Brzesc on the Bug River. From Brzesc, he

had 100 miles to go on foot to reach Pinsk. The land was

under Soviet control, but it was where his family was,

and it was the only home he knew.

At one point during his walk home, Soviet soldiers

stopped him and demanded he show his hands. The Soviets

were killing all military officers and intelligentsia so

as to remove all the leaders. Dyonizy's big, rough,

calloused hands let him live, and he got home.

When he got home, he found his hometown under the control

of the Russian Soviets. He worked where they told him to,

and they told him to work on the railroad. He befriended

another Polish man, and together they stole food from the

Russians. The food was moved on the trains, and Dyonizy

and his friend helped themselves, to feed their families,

and to feed some folks who were not supposed to be there:

Polish partisans, hiding in the woods. Dyonizy's friend

had a small wagon, and they used it to move the food.

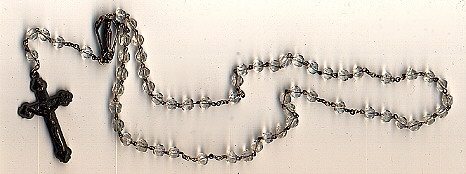

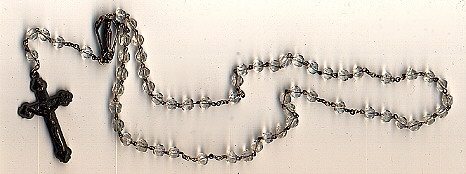

A year later in Pinsk, he married a local Catholic woman.

Officially, Dyonizy's religion was Russian Orthodox, but

he had little use for any religion; he viewed all

"men of the cloth" as bandits, but the woman he

wanted to marry was Roman Catholic, and Olga was not

going to accept less than what she could view as a valid

marriage. Olga could read and write and had graduated

eighth grade, and Dyonizy likely saw Olga as a little

"higher class" than he saw himself, so Olga's

standards were accepted. Dyonizy and Olga married in

front of a priest in a Catholic marriage ceremony in

March 1941. By doing this, they risked their lives since

religion was outlawed by the Soviet Communists who

controlled Pinsk. The priest promised that no papers

would ever be found to prove the two had married in a

religious ceremony. It is likely that the priest created

no paper trail. Paper was not necessary for the marriage

to be valid in the eyes of the Catholic Church; all that

was needed was that Dyonizy and Olga made vows to each

other in front of a Catholic priest.

Later in 1941 the German Nazis took control of Pinsk. The

Nazis kept Dyonizy working on the trains, and Dyonizy

kept liberating food that was being moved on the trains.

Once the Germans arrived, however, it became problematic:

His friend with the wagon was Jewish and was removed by

the Germans quickly. With no friend, there was no wagon.

Also, the Germans kept better records than the Russians.

Nonetheless, Dyonizy was able to continue with food

thefts.

In March 1942, Olga gave birth to a son, Victor. Sometime

while Dyonizy was living in Pinsk under Nazi control, he

witnessed a scene of Nazi soldiers going into a

community, ordering all of the people outside, separating

the people into two groups, and machine gunning the

people in one group. None of these people were Jewish,

according to Dyonizy. By then, the Jews had been removed.

Most likely, the Nazis got their point across: "We

are the rulers here, and you will live or die by our

choice."

Early in the second half of 1943, Dyonizy was confronted

by Nazis who knew he was stealing food, and who knew part

of the reason why he was stealing food. The Nazis gave

Dyonizy two bad choices: Tell the Nazis where the

partisans are hiding, and the people hiding surely will

be killed, or do not tell the Nazis where the partisans

are hiding, and the Nazis will kill Olga and Victor.

Dyonizy chose to betray his friends who were in hiding,

and they were killed. [Had Dyonizy told me this story, I

might not have believed it. Instead, I was told the story

after his death by his Polish friend and neighbor. The

irony was that, when the woman told the story, she had

absolutely no empathy for Dyonizy's plight. Over 45 years

after Dyonizy had been forced to make the choice, even

months after his death, this Polish woman could not

understand why Dyonizy had betrayed his compatriots, and

she spoke negatively of him because he had done so.

Apparently she had learned because of a confidence shared

by Dyonizy or Olga. If there had been any hope for

understanding or compassion, Dyonizy had not found it.]

On November 10, 1943, the Germans removed many Poles from

Pinsk. These were non-Jewish Poles; the Nazis had already

removed the Jewish Poles. Dyonizy, his wife, and son were

packed onto cattle cars and taken to Dachau, German. The

people were packed so tightly that they could not sit.

Dyonizy, Olga, and their baby Victor were at Dachau for

less than a month. Living conditions were unhealthy. They

slept in a triple-decker double bed, with one family to

one mattress. There was no running water. The baby got

diphtheria. The family was moved again, this time to

Augsburg, Germany, where the parents would be held as

forced labor (slave labor). The parents were put into

separate barracks. The baby was taken to what was called

a hospital. There were Catholic nuns at the hospital who

prayed for the baby. Perhaps they knew in advance what

would happen if the baby did not get well fast. On

December 31, 1943, Dyonizy and Olga were told to go to

the hospital to see Victor. A Nazi physician told Olga to

hold her baby as Dyonizy watched. The doctor gave Victor

an injection; the baby began convulsing immediately and

died. The doctor's response was to walk away as the

mother held her convulsing baby. While it cannot be

proven that the physician intentionally killed the baby,

that is most likely what happened. It was the last day of

the year, and orderly Nazis liked clean books. That New

Year's Eve, Dyonizy and Olga wandered the snowy streets

of the slave labor camp, crying.

When I was told this part of the story by Dyonizy, I said

in shock, "They killed Victor." It seemed

obvious. Dyonizy apparently had never been able to admit

that horror to himself. He looked stricken and said,

"NO! He had an allergic reaction!" The old man

then began pacing and twisting his hands. It was a horror

he could not admit even forty years later, even when he

was able to state the simple facts.

Victor, born 6

March 1942, died Dec. 31, 1943

By June 1945, the Americans reached

Augsburg, and the camp was freed. Three months later,

Dyonizy and Olga's second son was born. They named him

"Bogdan," Polish for "gift of God."

That name was popular among mothers who gave birth after

surviving Nazi slave labor camps.

After the Yalta Conference (where the Allies gave the

Soviets the part of Poland that the Soviets had invaded),

Dyonizy and Olga had no home to return to. The town that

had been their hometown was suddenly part of Russia. Had

they returned to Pinsk, Joseph Stalin's forces would have

had the Polish couple killed as traitors for having

"allowed themselves to be captured by the

Germans." Instead, they remained at the camp; it had

become a refuge camp under the control of the United

States Second Army.

In 1949, Dyonizy brought his family to America thru

sponsorship of Catholic Charities. They arrived at Ellis

Island and moved to Wisconsin where Dyonizy farmed an

American doctor's land for a year. Then he moved his

family to a small apartment they shared with another

family; he worked in a factory, and Olga cleaned offices.

Two years later, the two were able to buy a tiny house in

a Polish neighborhood. By American standards, it was not

much more than a shack, but it was their home.

Dyonizy spent his working years in various low-end jobs,

typically doing factory work or janitoring. Before the

days of the feminist movement, Olga worked because she

had to; she cleaned offices and worked in cafeterias.

It would be nice to leave the story here: Dyonizy

struggled hard for his family, bought a home, and worked

till the end. And it would be correct to say those

things, but it wouldn't tell Dyonizy's story completely.

Like many Nazi camp survivors, Dyonizy struggled with

depression and isolation most of his years in America,

particularly after Olga died of cancer. Two months after

the 50th anniversary of Poland's attempt to stand up and

fight back against Nazi Germany, Dyonizy ended his own

life. In the two years before he killed himself, three

other men in his community who were also Polish Army

Veterans and Nazi camp survivors had made the same

choice.

to a photo of Dyonizy and Olga

Dyonizy's parents and siblings

|